Surrealism and the Idea of the Avant-Garde

In attempting to consider, from the surrealist point of view, the relevance of the concept of the avant-garde and whether surrealism can be considered an avant-garde movement, I suppose that the simplest answer would be no. Surrealism is, in many ways, opposed to the idea of vangardism both politically and culturally, at least if we consider the traditional meanings of the term. (And that despite Peter Bürger’s claim that surrealism is the ultimate avant-garde). The cultural avant-gardes of the twentieth century are roughly divided between those that purvey what they consider to be the newest, most advanced form of art, literature, music – Fauvism, Cubism, Abstract Expressionism and so on, and those that have a broader cultural and philosophical programme, such as Futurism, Poetism, certain forms of Expressionism, advocates of a world-view rather than a merely formal radicalism. While surrealism was most certainly born out of the avant-gardes of the early Twentieth century, it claims to be different in kind.

Firstly, the cultural avant-gardes are concerned as much as anything else with novelty. The sensation of newness wears out very quickly and needs a newer new to replace the old new, to be replaced in turn as that new quickly wears out. Surrealism, which has survived for the best part of a century, can hardly be thought of as a novelty! Too often the avant-garde movements have been easily co-opted into reactionary political tendencies, Futurism in Mussolini’s Italy for instance.

The political vanguardism can often be too observant of the party line. In claiming to be in the van, the front line, the party then claims to speak for those others they regard as following their line. Political vangardism is, therefore, too frequently attached to the Identity Principle, attempting to homogenize what is, in fact deeply heterogeneous. Surrealism, in considering itself as always quite other, stresses its non-identity with all dominant ideology.

The resources of surrealism date back beyond its birth, the ancient principle of Analogy, Hermeticism, combine with modern thought (Freud and Marx being only the best known) as well as the ideas of extraordinary figures such as Fourier. It would be a great mistake to ever consider surrealism as some amalgam of Freudian and Marxist thought as both are held at some distance by this principle of non-identity. Surrealism’s close links with other movements are never a capitulation to the whole framework of that movement’s ideology, just as its approximation to those ideas is not merely eclectic. They create a frame of references that inform surrealist activity, allow it to develop along independent lines and to which surrealism can, at times contribute. The best image here is that of the constellation.

Another consideration is whether or not the concept of the avant-garde is to be thought of as at all current. Given that we live in a world that announces itself as “postmodern” – at least according to many – the term avant-garde seems irredeemably modernist to many. I do not wish to denigrate all that is termed postmodern. Like modernism, it has much that is good, much that is bad, and in any case, the term has been so abused as to be fairly meaningless unless one defines one’s terms very strictly. But the idea of the postmodern has taken over much that was the role of the old avant-garde, including, too frequently, an uncritical love of the new, in this instance, the embrace of the cybernetic rather than the paroxysms of the mechanical.

It becomes increasingly obvious when one considers the postmodern scene how what is thought of as ‘advanced’, for instance, in the arts, is often only so in the most superficial way, it has already been co-opted by big business, by power that it offers no real resistance to what the situationists called the Spectacle. The front line is only a front line of a mass of conformity. Surrealism, by contrast, has claimed to be a ‘microcivilization’. (See, for instance “La Civilisation Surrealiste” the result of collaborations between the Czech and French surrealists in the 1970’s, and organized by Vincent Bounoure and Vratislav Effenberger.)

It is in this concept of a microcivilization that a clear image can be seen of surrealism’s claim to its non-identity with the avant-garde, not the front line, but a principled desertion. However, I would also claim that surrealism’s abandonment of avant-gardism is in no way a simple retreat. I would, in fact, make the claim that it is a dialectical act of overcoming the idea of the avant-garde. Surrealism is the laboratory for an experiment in living. As such, it offers the possibility for a life directed by poetry, or rather a profound poesis. The antithesis of the avant-garde is, therefore, not conservative art or politics, but a virulent other that has absorbed the concept of the avant-garde as it has overcome it and point the way, not to the front line, but to the antipodes of the wreck of the civilization we all still live in.

Stuart Inman

London

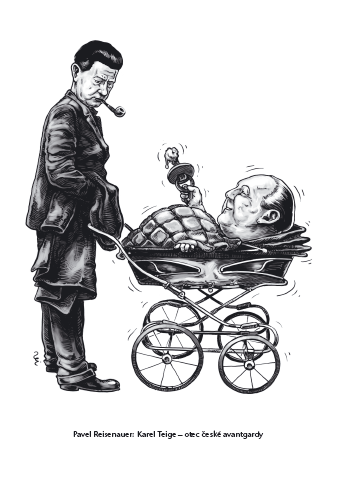

Otázka pro... ještě avantgarda?

Question for... the still-Avant-Garde?