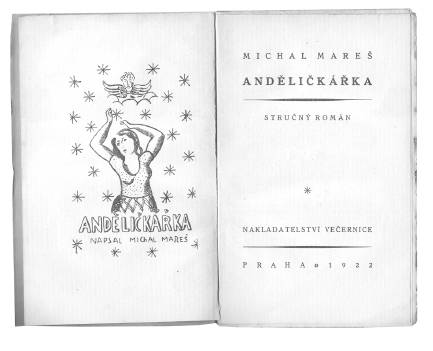

Michal Mareš

The roots of the idea of translating Michal Mareš’s little book reach back into the 1970s, when, shortly after being able to add the word andělíčkářka ‘(backstreet) abortionist’ to my Czech vocabulary, I coincidentally happened on a copy of this eponymous ‘concise novel’ in the then well‑known second‑hand bookshop in Dlážděná Street in Prague. The author’s name meant nothing to me and I was actually first drawn to the book by its cover. Added to that, however, this copy carried the author’s autograph and a dedication to a so far unidentified Božena Černá. The graphic elements of the publication, including the frontispiece, are attributed in the colophon to L., that is, Ladislav Süss, whose work adorns numerous publications by several other period publishing houses in Prague.

Süss was a founding member of Devětsil, and this milieu of avant‑garde promoters of ‘proletarian art’ suited the young Mareš very well. Many of them also published with the same house, which was Václav Vortel’s (1877–1939) radical left‑wing Večernice. By 1926, when the company, following all sorts of ups and downs and changes of name and proprietor, basically folded, it had published some thirty titles, including Mareš’s early prose works and the poetry of Jaroslav Pokorný (1899‑1940), later to become the author of many popular adventure novels and literature for women and girls.

After I had read the book, it occurred to me to translate it, and for a number of different reasons, first among which was to create a parallel text to have available for students. In due course I did make it available to them as a self‑help learning tool; there were few Czech‑English parallel texts in existence (though there are plenty of English‑Czech ones, mostly of English classics), and in the past I had appreciated the existence of similar publications based on German or Italian. This David Short 250 little work seemed ideally suited to the purpose, since it is fairly short and the language not too archaic while containing authentic instances of a number of grammatical features that the foreign learner has to know and recognise, even if s/he will never use them actively (for example, the transgressive – aka gerund or verbal adverb); in later literature they are scarcer (with notorious exceptions in those writers who make conscious play of their use) and today they would be described as ‘(highly) literary’, belonging generally, if not quite exclusively, to the higher realms of style. In no way, however, can Andělíčkářka be accused of being high literature.

The resultant translation, first done sometime in the 1980s, was meant to be a kind of compromise between the literary and the literal in order to facilitate access to the language of the original for the English‑speaking learner of Czech. The only departure from this principle is the extended passage from Jonathan Swift’s satirical pamphlet, A Modest Proposal for preventing the children of poor people in Ireland, from being a burden on their parents or country, and for making them beneficial to the publick (1729). Here I used Swift’s original text, when serves in turn as a chunk of English‑Czech parallel text that might also be handy for the English‑speaking student of Czech – or indeed the Czech‑speaking student of English.

Sometime in 2004, Mike Leigh made a film about an English working‑class abortionist, Vera Drake, which immediately won a number of awards. Subsequently, the problem of how to ‘help women in their hour of need’ was raked over almost daily on BBC Radio 4, chiefly, but not solely on ‘Woman’s Hour’. This led me to return Mareš’s Andělíčkářka, make a few amendments to the English text, resolve a few other little snags and think about publishing it somehow; after all, despite its 1922 publishing date and a different, that is, Czechoslovak, criminal law and suchlike, it was nothing short of topical. Mareš’s Hedvika Michovská is, despite the difference in class background, a worthy forerunner of the worthy Vera Drake.

Despite everything, the translation remained in my bottom drawer or the computer’s memory, though students continued to be exposed to it as required. However, out of the blue, one former student, Mike Tate, conceived the idea of publishing Andělíčkářka in print and on the internet. To which end, with the collaboration of another former student, Jan Barker, otherwise an importer of dictionaries and textbooks (including those for Czech), a publishing house was created and Andělíčkářka should appear this June at the latest – as the first publication under the Jantar imprint. I find this extremely pleasing – and found no less pleasing the discovery that Slovo a smysl had suddenly had the selfsame idea.

But who was Michal Mareš? According to Václav Černý: ‘A poet, prose‑writer, literary adviser to theatre and film companies, and, above all a journalist.’ According to his indefatigable promoter Pavel Koukal: ‘[a man with] a dangerously profound sense of the truth, justice and human liberty.’ On the title page of his posthumously published memoirs Mareš describes himself as an ‘anarchist, reporter and war criminal.’ (Ze vzpomínek anarchisty, reportéra a válečného zločince. Prostor, Prague 1999).

He was born in 1893 in Teplice, North Bohemia and grew up in Prague. The anarchist streak in him soon came out and he was expelled from school for protesting against the execution without trial of the Catalan free‑thinker and anarchist Francisco Ferrero i Guardia. In Prague he mixed with other anarchist and left‑wing elements, such as Jaroslav Hašek, for whose Party of Moderate Progress within the Limits of the Law he took the minutes of meetings held at the Golden Litre pub. His journalistic aspirations took him to Hamburg, Berlin and further afield to Italy and North Africa, where he spent a while with the Foreign Legion. He was literary adviser to Artur Longen’s Revoluční scéna (Revolutionary David Short 252 Stage) and a correspondent for various Prague papers – Tribuna, Prager Tagblatt and Rudé Právo. During the war he helped organise an illicit postal service into Theresienstadt and was active in the resistance. Because of a serious misunderstanding based on two like‑sounding names – of an innocent former Prague‑German journalist and deserter from the German army, and of a German informer and member of the German security forces – Mareš was arrested by the NKVD and might have been despatched to Siberia, possibly never to return. Fortunately, the mistake was explained in time, Mareš was released and even received a formal apology from the Soviets. After the war he had more problems, this time with the StB (Czechoslovak state security), who took a dislike to his frankly critical articles in Dnešek, and after what came to be known as ‘Victorious February’, that is, the Communist takeover in 1948, he was the first to be expelled from the writers’ union, then he was imprisoned for seven years for, amongst others, defamation of the Soviet Union and a fabricated charge of a war crime – hence the title of his memoirs. On his return from prison, he had barely any chance of publishing and became almost totally forgotten. He died in 1971.

In earlier times, however, besides numerous contributions to the period press, he did write, in a manner of speaking, semi‑professionally, first translating the poems of the like‑minded Petr Bezruč, then publishing his own social prose‑poems at his own expense. After one more collection he switched to prose, producing a colourful mix of sketches, reportages and commentaries, with the odd novelesque gem a la Andělíčkářka or the longer ‘revolutionary’ novel (e.g. Pan Václav, český trhan v cizině [Mr Vaclav, a Czech tramp abroad], 1918) thrown in for good measure. His association with Longen’s theatre bred his single play, Sing‑Sing (1929), which was a response to the controversial execution for murder of two Italian anarchist immigrants in Massachusetts in 1927.

As for Andělíčkářka, Mareš is clearly content with a simple, not to say bare‑bones narrative. The plot indeed has the potential dimensions of a novel, but is condensed into the ‘concise [actually highly condensed] novel’ of the sub‑title. He helps himself out generously with the interpolated stories, or letters, of his secondary characters, his protagonists barely develop, though some diversity is added by a handful of graphic tit‑bits, such as the musical notation for a fire‑engine’s siren, and the odd flash of humour (in how the death of Hedvika’s husband is told). The journalist in him is never far to seek – in fact the whole ‘novel’ is really an anarchist pamphlet given form as fiction. When he believes that a thing is right, he 253 překlady – translations believes so absolutely: the main argument about the necessity (or shamefulness) of abortion goes as far – where it is too late for an abortion to be the answer to a woman’s ‘problem’ – to accept post‑natal murder as right. The living successor to Hedvika’s philosophy proudly bears the name Parchant (Bastard), and the final image of him is that of the absolute anarchist revolutionary. At the end of his ‘concise novel’ Mareš has confirmed himself as a pure, tub‑thumping, soapbox orator in the simplest vein.

And yet this curious little book is worth reading.

The Angel‑maker will be published in June 2011 by Jantar Publishing in London. At the same time the same publisher will issue Daniela Hodrova’s I see a city… (i.e. a translation of her Město vidím…), translated by David Short, with a Foreword by Rajendra Chitnis.